Twenty-one days without the internet

Info Exame Brazil, March 2014

(originally published in Portuguese)

The act itself was simple. At 4pm on December 14, 2014, I unplugged my router and turned off the 3G on my iPhone, to spend 21 days without the internet. I’d chosen the timing carefully. With the end of the year looming, work was winding down. And it seemed a good time to put into practice an experiment I had been thinking about for most of the year: to see what life would be like away from the constant stream of digital data with which many of us now share our lives.

The first 24 hours were hopeless. I’d set an out-of-office message on my email, asking people to call or SMS me, and I’d printed off a few weeks of my Google calendar, but otherwise I hadn’t prepared at all.

I had to keep on reconnecting to get things that I had forgotten. It was eye-opening how much of my life existed in the cloud: bank statements and receipts for my end-of-year accounts, reference numbers for purchases I had made, phone numbers, files on Google Docs, and so on. All of these I had consigned to the net on the basis that I could easily get them whenever I wanted. Unplugging had removed them from my grasp.

After a few days, though, things had settled down and I started to notice a change in the quality of my time. In my connected life, I would use the internet to fill the little gaps between bigger activities – checking for messages, reading something on Gawker or Buzzfeed, browsing my emails just because they were there.

Now those gaps became more meaningful in themselves, as times to pause, relax and think a little. At a bus stop, instead of poking around on my phone, I would just stay quiet for a few minutes, like a mental yoga session. To begin with it felt odd and boring. But, by not forcing myself to think of anything in particular, my mind became less cluttered and my thoughts became slower, gentler and more profound. Bigger issues came to mind, the things you think about on holiday but for which there seems to be too little time when you come back into the busy everyday world. I started to carry around a notebook to jot down decisions I made in these moments – and I have acted on almost all of them since then.

I also started to see the world differently. Walking along the street without my phone in my hand meant that I looked at real things in a more attentive way and the world fell into a sharper focus. I’m not sure why this should be. I think it was because I was concentrating on things and people that were 20 metres in front of me, rather than on a tiny screen. But I think I also benefited from a psychological effect: by removing the digital world from my consciousness – none of that wondering whether I should log on and check something – I allowed my brain to focus much more on what was literally in front of my eyes. Colours became more vibrant and I started to notice things about my home town, London, that had previously escaped my attention. It was like being a tourist in a new place for the first time.

I spent most of last year thinking about our relationship with technology. I write for Wired magazine but I also teach, in London and São Paulo, at The School of Life, which tries to help people live life better, and at the latter I was meeting people who had been negatively affected by the technology world that Wired loves to celebrate.

A phrase came to my mind, coined by Henry David Thoreau, the 19th-century American philosopher who was observing the unexpected negative effects of the first industrial revolution: “Men have become the tools of their tools.” We invent something and then we become the slaves of it. Now, a quarter of a century into a the digital industrial revolution, it feels like we are making the same mistakes.

It’s not that humans are fools, far from it. It’s just that we can be so excited by new technology that we feel we have to engage with it unquestioningly, even if that makes our experience of life poorer.

I noticed this especially, during my unplugged 21 days, when it came to listening to music.

I am a huge fan of Spotify. I love its infinite-jukebox capability, the fact that I can think of a song and pretty much immediately play it on my Mac. I often flit from track to track, following up recommendations of others or using the Radio feature to discover new artists. This feels good at the time, but, looking back, I don’t think I remember many of the new names I listened to and I certainly don’t think I have in some way broadened my music collection. Instead I have heard a large number of songs in a fairly random order.

Unplugged, all of this was unavailable to me and instead I rediscovered my CDs. By a fluke of disrepair, the track selector on my CD player was broken, and I could only play CDs straight through from beginning to end – just like we used to do with vinyl. This was a surprisingly pleasurable discovery and something I stuck to even when I remembered I could play CDs (and choose tracks) on my Mac. Instead of jumping from track to track, sometimes even before they had finished, I let an album play all the way through, listening to the music in the order that the band, composer or producer had thought hard about. I sometimes felt impatient for the instant skip or the jump to a related artist that the internet gives us, but that was easily compensated for by the pleasure of experiencing something that had been “curated”, to use that ugly online word, by someone talented who had thought hard about what track to put after what, a selection made by a human, not an algorithm.

By week two, I was barely noticing that I wasn’t on the internet. Out in the streets, I was enjoying not having Google maps and I rediscovered an old skill we used to have before smartphones became ubiquitous: planning a route on a map and holding that route in your head as you navigate the city. Thinking of journeys in this way – rather than the fragmented, “turn right”, “turn left” of GPS – made my city’s geography come alive again and fill with meaning. I began to think again in terms of north, south, east and west, about landmarks and distances, about the city has a whole. Journeys became more like adventures again, rather than dully necessary ways to get from A to B. Rediscovering the brain’s ability to hold even quite complex geography in mind was a timely reminder of the amazing operating system in our heads, something we can easily forget in our obsession with processor speeds and Big Data algorithms.

The US psychologist Martin Seligman has taken a special interest in what he calls core human strengths – the apps, if you like, that run in our brain, things like creativity, curiosity, bravery and leadership, that technology is quite poor at. I found taking time off the internet provided an opportunity to rediscover these and cultivate them in myself.

Not looking at my phone in conversations with others let me give them my full attention, and as a result the conversations were deeper and more fulfilling. Talking through a question with a colleague, rather than rushing to Google to find an instant answer to something, helped us both grow in knowledge and insight. By setting the internet to one side, I was rediscovering that we, as humans, are actually pretty smart.

In fact, the absence of Google was the most noticeable change during my 21 days offline. I was shocked by how much I used (and therefore missed) Google, not only tools such as GMail, Google Docs and Google Calendar, but the basic Google search too.

In the early days of the web, companies such as Compuserve and AOL tried to set up portals through which we would access a kind of filtered version of the internet, curated by them. These didn’t survive long and, on their demise, we celebrated the “fact” that the internet could never be ringfenced like this. But somehow, perhaps because it has been much subtler about it, we have allowed Google to do just this. Only when I didn’t have Google did I realise how often the Google home page was my starting point for researching something online. And if Google chose not to show me a site or a piece of information in response to what I am looking for – a worry that we had about Compuserve and AOL – I almost certainly wouldn’t notice the omission.

When I went online again after 21 days, the first thing I saw was a Buzzfeed link someone had sent me of funny local-paper headlines from around the UK. I usually like these things: they pass the time and they are pretty funny. But, being away from it, I found my expectations of the internet had grown and I realised I wanted more from it than just recycled humour and pictures of cats.

I realised that I could take much more control over what I saw on the internet and what I ignored, developing a relationship with it that was more measured and grown-up. The new sense of time I had gained by not being online I now wanted to preserve. And I liked things like having the map of my city in my head.

This was the real lesson of time offline: the real world is incredible but it is often eclipsed but its flashy digital counterpart that is constantly calling for our attention. I think the time has come to put the internet in its place, as a tool we use to do amazing things, but just as that, as part of a bigger world that I have rediscovered is just as stimulating and exciting.

How to renegotiate our relationship with the online world

1. Retract

The idea of “always on” was invented with the invention of broadband and we can always uninvent it. Twenty-one days is a long time offline, but how about a few hours, a day, a weekend? Experiment with disconnecting completely from the internet for periods of time and see what emerges to take its place. You might be pleasantly surprised.

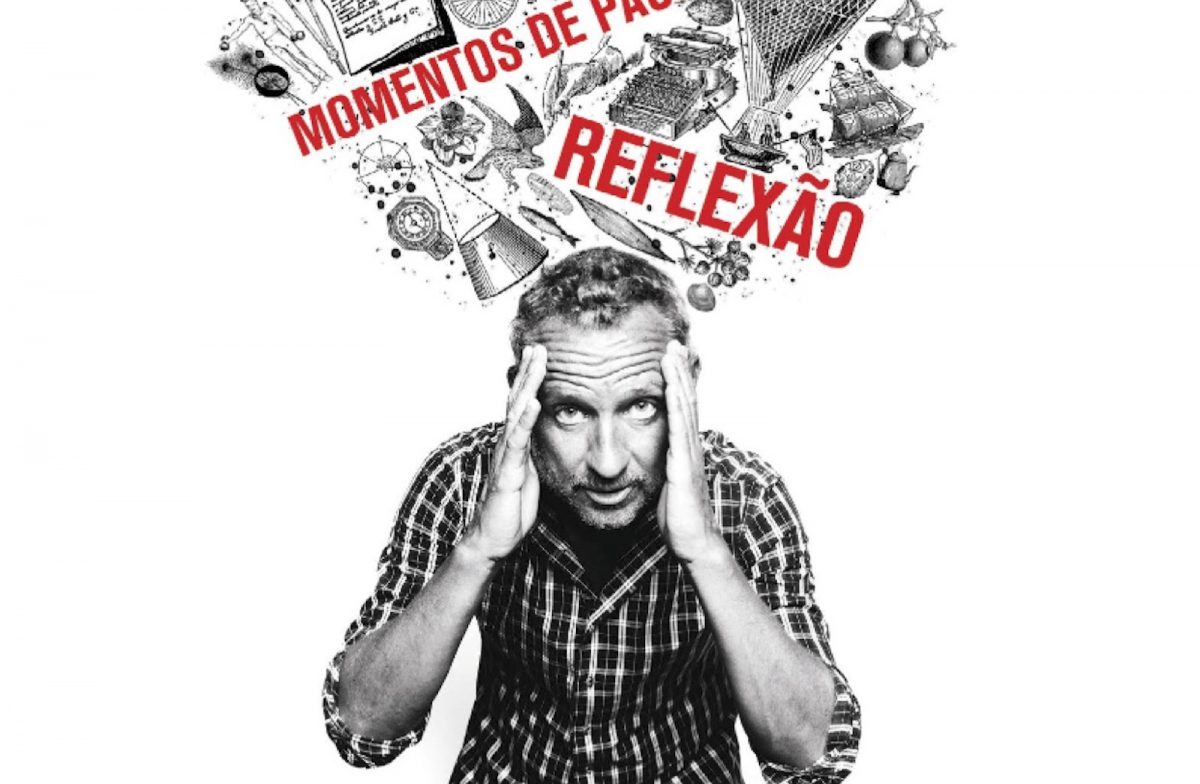

2. Reflect

With this new offline time in your life, start to notice what’s important to you and gives you pleasure, maybe conversations with friends, losing yourself in a book, exploring your city with new eyes. Take Martin Seligman’s online questionnaire at authentichappiness.org to discover what you are especially good at. Take time to think of what you value in life and what your sense of purpose is.

3. Return

With this new knowledge, come back to the world of technology and see it is a set of tools that we can choose from rather than a collection of apps, social networks and sites we have to keep up with. Experiment with times of day when you are online and times when you are disconnected. That way you we can regain control over technology.