The Johari Window can throw light on how organisations are seen and see themselves

Monthly column: “Possible Futures”

Época Negócios Brazil, August 2022

(originally published in Portuguese)

The foundation of good emotional and mental health is self-knowledge – understanding how we think, behave and react to situations, and understanding why we do those things. And a really useful tool that can help us understand ourselves (and others) better is the Johari Window.

The Johari Window was designed by two psychologists in 1955 (its name is an amalgamation of their first names: Joseph and Harrington) to help people gain an insight into how they see themselves and how others see them.

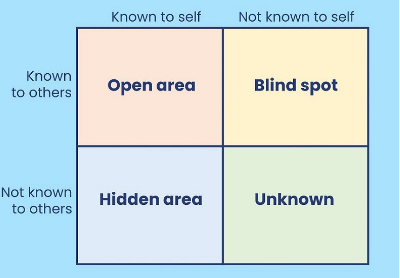

It divides the emotions, attitudes, dreams, qualities and skills that make us what we are into four segments.

In the top left are the things that we know about ourselves and which other people know about us too. At work, these might be things like the fact that we tend to keep calm when things get stressful or are often able to see alternative solutions to problems. Our colleagues see those things in us and acknowledge them.

To the right of that is what we might call our blind spot. These are things that people “know” about us but we are not aware of ourselves.They are sometimes positive qualities, perhaps skills and talents we don’t realise we have, and sometimes negative aspects of ourselves that can be unsettling to discover.

Bottom left is the area of things that we prefer to keep private. These might include aspects of our family life or financial situation, or they might be things we are embarrassed about and don’t want others to know. Imposter syndrome, which is something all of us experience at one time or other, is very much connected with this hidden area. We can expend a lot of energy trying to ensure that other people don’t discover what is in it.

In the bottom right is what Freud would call the unconscious – the parts of our mind and character that are invisible to us and to others, but which still have a strong effect on how we think and behave. We may, for example, become incredibly annoyed by a talkative colleague or overreact to certain setbacks that seem to leave others unfazed. These responses don’t come from nowhere. They are reactions that the unconscious part of our brain is making, without us being aware of the reasons behind them.

One of the huge benefits of the Johari Window is the opportunity it gives us to increase our self-knowledge – to move the vertical line to the right, so we know more about ourselves; and, should we choose, to move the horizontal line downwards, which allows us to share more about ourselves with others and help them understand us better.

There are many ways to move these lines. An open and intimate conversation with a friend or a colleague can help us discover things that people know about us but which are hidden to ourselves. Psychotherapy can help us explore the unconscious parts of our mind. Coaching or mentoring can give us an opportunity to talk about the parts of ourselves that we are keeping hidden and reconsider the hold they have over us. Obviously, all of us have parts of ourselves that we don’t want to share with others. But hiding things takes mental energy and it’s worth asking why we don’t want to be open about them. Discovering, for example, that everyone suffers from imposter syndrome can help us acknowledge the times when we feel it ourselves.

The Johari Window is also a very powerful tool for helping teams and organisations explore how they see themselves and how they are seen by others. As part of what we might call “company coaching”, the Johari Window can throw light on differences between an organisation’s perception of itself (its brand, top left quadrant) and how customers, suppliers and other stakeholders actually see it (top right).

Exploring the bottom left quadrant can lead to frank internal conversations about ways in which the organisation thinks and operates that it feels it needs to keep hidden from outsiders. Just as in individuals, this hidden set of ideas takes energy to maintain and often uses up a huge amount of time – time that could be more happily spent helping the company grow.

Whether teams and companies can have an unconscious in the Freudian sense is a matter of debate. But all organisations have ways of thinking and acting that are somehow ingrained in their identity, often handed down informally from senior to junior staff, and bringing these out into the open can help everyone ask if these unwritten norms are still worth adhering to.

Greater self-knowledge is a hugely powerful emotional skill. The more we understand ourselves, the more we can build on our strengths, reduce the irrational reactions we sometimes have to situations and cut the amount of energy and time we spend being anxious about things. And the more we are open about what is going on in our minds or in our corporate ways of thinking, the more easily others – friends, colleagues, customers, suppliers and stakeholders – can interact and do business with us.

The Greek philosopher Socrates famously said that the unexamined life was not worth living. Thanks to two psychologists from the 1950s we all – individuals, teams and whole organisations – now have a useful tool to start the business of self-examination and move towards a happier, better and more productive life – both at work and in our non-work lives.