Critics say that male circumcision is unnecessary and barbaric. Advocates claim it has many benefits

The Times, 24 March 2008

Barbaric, mutilation, child abuse, freaks, nutters, obsessives. The language on both sides of the debate about infant male circumcision is not always temperate. Put together new-born boys, their penises, knives and two of the world’s oldest religions and passions are likely to run high.

While last month saw the fifth International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation, marking a fairly united global campaign against the practice in females, the arguments about the removal of a male infant’s foreskin seem mired in misinformation, accusations and despair.

What is clear is that there are very few medical indications nowadays for choosing circumcision over other procedures.

Writing in the BMJ (British Medical Journal) last December, Padraig Malone and Henrik Steinbrecher, of Southampton University Hospital, found only two absolute indications for circumcision: a chronic skin condition called balanitis xerotica obliterans, which may have links with penile cancer, and some specific abnormalities and scarring on the foreskin. Beyond that, they say, problems such as phimosis, when the foreskin is too tight to be pulled back over the glans, and inflammation of the glans and foreskin caused by bacterial infections – both of which often see the surgeon reaching for their scalpel – can usually be treated non surgically.

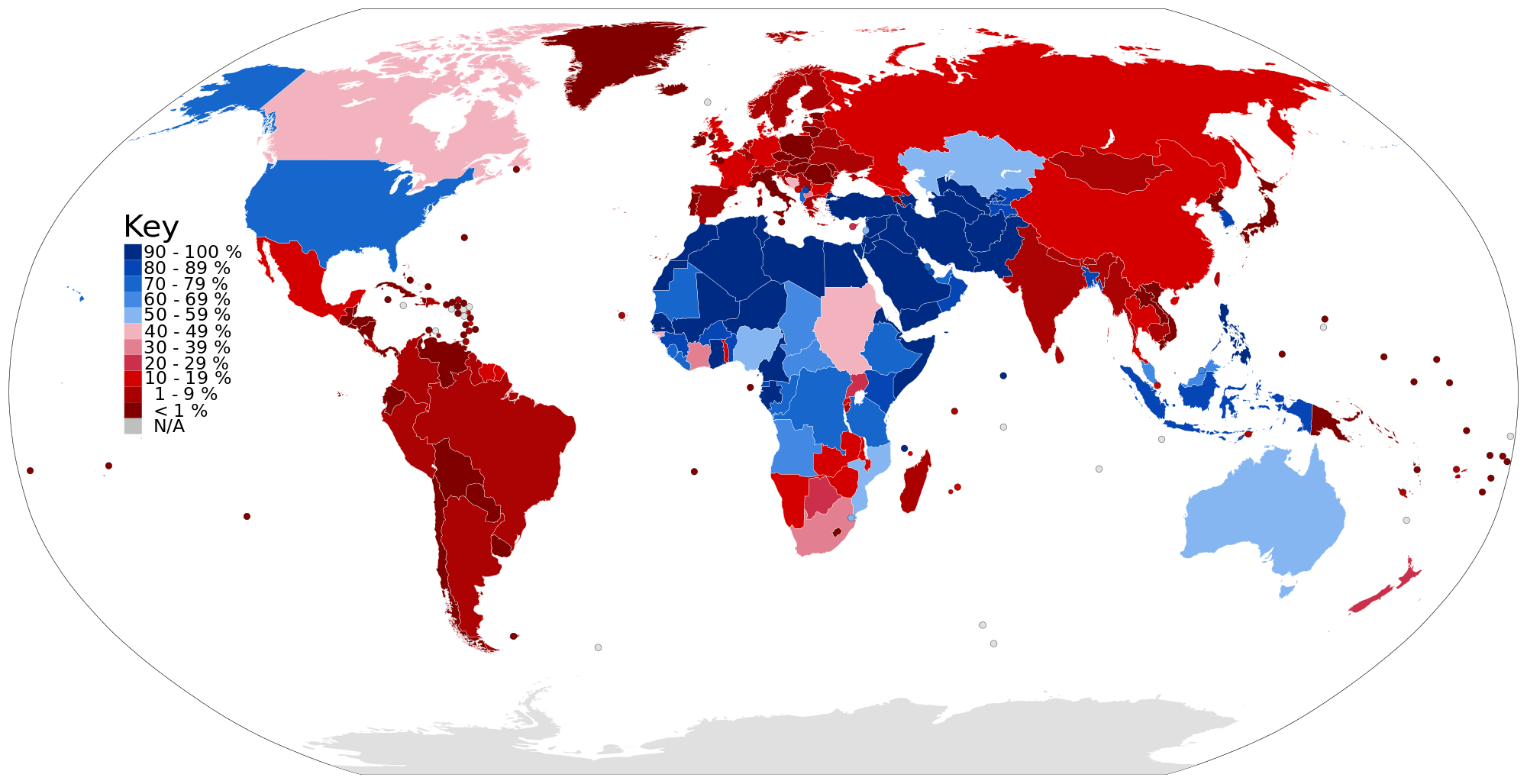

Yet infant male circumcision continues on a wide scale. According to Malone and Steinbrecher, one male in six worldwide will be circumcised at some point in his life. In the UK, rates have dropped significantly since the 1930s and 1940s, when it was almost de rigueur for boys of a certain class to be circumcised. But today the NHS still performs about 10,000 circumcisions a year on boys aged up to 15. Add to that hard-to-count religious circumcisions carried out at home and, say campaigners against it, you end up with a lot of unnecessary trauma and risk.

“Many men are damaged by it,” says David Smith, general manager of Norm-UK, which campaigns against male circumcision, “both physically and psychologically. The physical harm includes problems with sensitivity – either they have no sensitivity or too much ‘bad’ sensitivity. The psychological damage is that men who are circumcised feel very different and can even suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.”

However, circumcision does appear to offer some important health benefits, particularly with sexually transmitted infections. Research published last year from Kenya showed that circumcision had a significant protective effect against HIV infection – at least in countries where HIV is extensive and spread predominantly through heterosexual intercourse. Penile cancer also appears to be less common among circumcised men. And a 1999 review of past research, published in the British Journal of Urology, indicated that uncircumcised males were more prone to diseases such as syphilis and herpes simplex. Which is enough to persuade some doctors that circumcision is the right course.

“When my boys were born,” says Dr Kirsten Patrick, a former hospital doctor and now an associate editor at the BMJ, “I did an enormous search of the literature and I thought circumcision was a good thing. It is much easier to do when they are small and less traumatic than waiting till later. I knew as a doctor that there was a way that they could go through this pain-free.”

Patrick has no truck with circumcision away from the medical establishment. “Holding a baby down, with no anaesthetic, that’s dreadful,” she says. “There’s no way anyone should do that. But I am in favour of saying that there is benefit to circumcision and it should be regulated.”

One part of the country that is moving quickly in this direction is Walsall, where the local hospital now offers a weekend male-circumcision clinic. “We have a large Muslim community here,” says Dr Sam Ramaiah, director of public health for Walsall Primary Care Trust, “and we wanted to provide local children with a service that is safe and secure. The procedure takes place in hospital with local anaesthetic and is done by a trained surgeon. The advantage is that there is care available in case of complications and, if necessary, the child can stay in.”

Programmes such as this are unlikely to satisfy anti-circumcision campaigners – who say that the physical effects of circumcision on an infant are only part of the story. Norm-UK’s argument is that, for many men, circumcision reduces sexual pleasure and that the trauma of childhood circumcision can last a lifetime. “Circumcision is not like having your tonsils out,” says Smith. “You are physically different from a normal man and you start to shy away from using changing rooms or undressing in public. It affects men in relationships. They feel inferior.”

As evidence, he e-mails me the transcript of a lecture he gave last year, entitled “Circumcision: The Hidden Damage”, which includes a range of quotes from men blaming parents and doctors for the “mutilation” that they were subjected to as children. Yet his sample is inevitably self-selective, being made up of men who had already contacted Norm-UK for help.

“The psychological side of this debate is not easy to pin down,” says Andrew Samuels, professor of analytical psychology at the University of Essex and a psychotherapist. “If it were possible to generalise accurately about the impact of infant circumcision you should be able to research it and find evidence of trauma in the circumcised population. But the research has not been done. So we are in a kind of not-knowing state.” But, he says, “it may well be a bigger act, more problematic, more potentially upsetting, not to circumcise in a culture that circumcises. I don’t think many Jews, for example, would deny the physical pain (of circumcision) but they might say that not to do it could lead to a psychologically distressing situation in which an uncircumcised boy might be denied a place in the group.”

Jonathan Romain is Rabbi of Maidenhead Synagogue and chairman of the Assembly of Rabbis, which oversees Reform Judaism in the UK. (No one from the more orthodox branches of Judaism or Islam responded to requests to be interviewed for this piece.) “Even the most lapsed Jew will circumcise his or her son, but there have been changes in the past 20 years,” he says. “In the wider society, circumcision is going out of favour. In the Jewish community there has been an increase in intermarriage and sometimes the non-Jewish partner has objections.” Romain, however, has no doubts about the safety of the procedure.

“If there was any hint that there was a physical or psychological problem it would have been suspended centuries ago, something that has happened to other practices in Judaism. And indeed things have changed already. Nowadays we will use only mohelim (people who perform ritual Jewish circumcision) who are doctors. We always use anaesthetic cream. If there is anything that indicates that we should delay the circumcision we will delay it,” he says.

Samuels, who is Jewish, feels it is time for a discussion within Judaism about how central circumcision is to Jewish identity. But he acknowledges that to get a frank discussion will need people to stick their necks out.

“Things will change,” he says, “but over a fairly long time scale. In 25 years there may be plenty of uncircumcised Jews who will identify as Jews and be accepted as Jews and that won’t depend on their being circumcised or not.”

Others are not so sure. Ritual circumcision stretches back before the origins of Judaism and Islam and is so entrenched in those religions that it will take a lot to shift it.

“It can come as a surprise to many how custom and tradition are still powerful forces in liberal, secular societies,” says Justin Woodman, a lecturer in anthropology at Birkbeck College, University of London, who specialises in the anthropology of religion. “Circumcision is part of the politics of identity in a diverse and multicultural world. The act of cutting literally makes a line of division.”

John Turner (not his real name), a 60-year-old training manager from Birmingham, felt so affected by the fact that he had been circumcised as a boy that he is now taking steps to reverse the procedure. “I discovered I was circumcised when I was 4 and from that moment on it felt wrong,” he says. “As an adult I experienced a lack of sensitivity in my penis during sex. Then one day I saw an article on foreskin restoration in my son’s Maxim magazine and I thought, ‘Whoa!’”

Restoration of the foreskin takes many forms, but one of the most popular – the one that Turner is now using – involves stretching the skin of the shaft of the penis up over the glans and securing it there to encourage new growth.

The idea, according to Norm-UK’s Peter Ball, a former GP who himself has undergone foreskin restoration, is that skin under tension produces new skin. “It’s a long process,” he says, “perhaps two to three years, and it requires dedication, but it results in a new foreskin, the glans becomes shiny, thinner and much more sensitive and sex is much more pleasurable.”

For Turner, there is still some way to go but, he says, “you have benefits as soon as you have some coverage. I don’t blame my parents or anything and I don’t think I have had psychological problems over it. I just lost of lot of sensitivity and now the glans is becoming sensitive again and intercourse is a lot better.”